In a recent interview with Jordan Peterson, the writer and self-confessed anarchist Michael Malice confessed that he could not for the life of him understand the rationale behind the wicked crimes that were perpetrated by the grooming-and-rape gangs in the UK, which has received so much media attention recently owing to Elon Musk’s re-exposure of it.

Peterson then gave his explanation for the gangs’ behaviour: that the gangs were possessed by the “Spirit of Cain” – a phenomenon he’s talked at length about several times. The paedophile rape gangs, so says Peterson, demonstrated a contempt for the world so deep that their logical expression of that contempt was to take the most innocent, most undeserving people they could find, and do the worst possible things to them. To wit, kidnap, drugging, rape, gang-rape, torture, and fustigation. The contempt that drove this behaviour is a manifestation of that contempt that drove Cain, a man whose efforts got him nowhere in life, while his brother Abel seems to have his efforts rewarded. When God tells Cain that he should look to himself for the reasons his offerings have failed, Cain receives all of the logical rationale he needs to murder his brother, who represents his ideal.

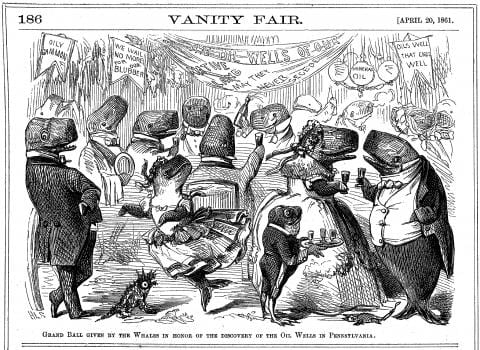

My Dearly Beloved Bean, one of the hosts of Chronscast, has recently been reading Moby Dick, Herman Melville’s masterpiece (which I’ve written about before). The book features various documentarian-style interventions throughout the book detailing the particulars of the whaling industry. Bean told me he struggled with those chapters that go into quite gruesome detail about how the whale is slaughtered and butchered. It’s rough, it’s brutal, it’s cruel, and it’s visceral. I feel these passages are sobering, but I always understood the rationale behind them; whaling was a industry, and a vital one, and one whose cruelty was eventually superseded by advances in technology that allowed people to burn coal and oil rather than blubber.

What is interesting is that this picture of the whaling industry is the framing device for a story of cruelty and madness, where Ahab seeks to destroy the thing that has taken a chunk out of his life. The White Whale in Moby Dick has been interpreted as many things by many writers over the years: a blank canvas, the fledgling America, a projection screen for the psychopathologies of the onlooker. For me, the White Whale is a dragon. It is both beautiful and terrifying, a source of danger and reward, and a meta-predator that can drag you down to the abyss, a la Jonah (Walt Disney made the whale/dragon representation more explicit in his 1942 masterpiece Pinocchio, where Monstro the Whale literally breathes smoke and flames after Pinocchio lights a fire in his belly).

The orderliness of Melville’s descriptions of the cruelty of the whaling industry serves to highlight its mundane nature in some ways. It’s cruel, but not sadistic. The men on the Pequod do not revel in their dismantling of the whale; it is simply a job that needs to be done. There is no sense of sadism among the crew.

Sadism. There’s a word and a half. I never really thought about the definition of the word sadism until I finished reading The 120 Days Of Sodom, the Marquis de Sade’s most notorious work, and from whence the word “sadistic” was derived. I’m not really a fan of trigger warnings. My erstwhile thought is that most people should be able to deal with stuff in a book, and that confronting dark episodes in books gives us a better understanding of the world. Grow up, man up, whatever.

But The 120 Days Of Sodom? Serious fucking trigger warning.

A few books stay with you after you’ve read them for their power, their emotional suckerpunch, their profound storytelling, or charismatic characters. But nothing has stayed with me as much as 120 Days… for pulling the reader into the absolute pits of morality, depravity, vice, and evil.

A quick precis, for those who haven’t read the book. It’s a novel, with a story arc of sorts. It features four main characters: the Duc de Blangis, the Bishop of X (and brother of the Duc), the President de Curval and the financier Durcet. These characters are libertines, and their intent is to explore, by degrees, the various different sexual “passions” – and the natural limits of those passions – that humans (overwhelmingly – but not exclusively – men) are possessed by, and what they do to achieve satisfaction via these passions. The story begins by introducing our four “heroes” as de Sade describes them, and their plot, which is to assemble a retinue of people with whom they will spend the winter at the Chateau de Silling in the Black Forest. These people include: very well-endowed men, beautiful prepubescent children (boys and girls), beautiful teenage virgins, beautiful young adults, duennas, and broken-down old prostitutes, the more disgusting the better. The manner in which these people are kidnapped is described in great detail, and makes for among the most upsetting passages of the book. The distinction between the beautiful and the disgusting is important. Among the children are the four heroes’ own daughters, who are given to one another as brides. With the people in place, each of the four prostitutes spends a month relating their experiences of the various perversions and passions they’ve encountered during a lifetime of being on the game in late 18th century France. They present 5 passions each day to the four libertines, who then spend the evening discussing those passions and finally re-enacting them with their captives.

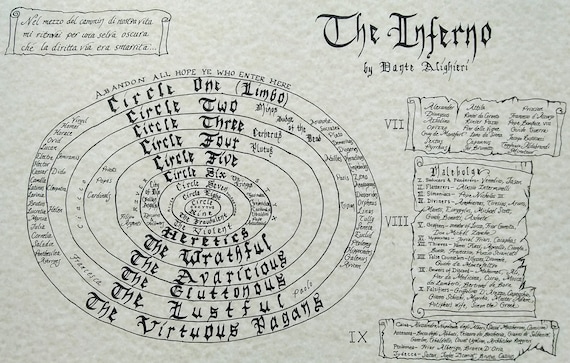

120 days, 5 passions a day, that’s 600 passions, divided into 4 clear sections, each marked by a thematic escalation: the Simple Passions, the Complex Passions, the Criminal Passions, and the Murderous Passions. De Sade provides meticulous detail of every single one. This type of “shopping list” approach to writing would quickly become dull, but De Sade is nothing if not organised. He orders the 600 passions so that they escalate, by degrees, in terms of their depravity, cruelty, and wickedness. Peterson, a personality psychologist, also says that creative or open people chase the edge of novelty, because doing the same thing quickly loses its sense of fun. It requires variation to keep the game fresh.

“‘There’s nothing to be wondered at there,’ said Durcet, ‘one need but be mildly jaded, and all these infamies assume a richer meaning; satiety inspires them in the libertinage which executes them unhesitatingly. One grows tired of the commonplace, the imagination becomes vexed, and the slenderness of our means, the weakness of our faculties, the corruption of our souls leads us to these abominations.’”

De Sade may be filthy, but he’s not stupid. He understands that perversions do not stand still in the mind of the pervert. The Simple Passions are gateway drugs to harder stuff. The stories told by the four prostitutes feature several recurring characters. One gentleman who begins by “mistreating” women’s nipples, progresses to cutting nipples off entirely. He eventually graduates to buckling a small iron pot over each breast and lowers the woman over a stove, and the woman perishes in agony.

It is this sense of orderly exploration that caused Freud to cite the book as evidence supporting his theory of the anal phase of human development, which leads to anal retentiveness and an obsession with putting things in their proper place. De Sade takes this literally, and the proper place tends to more often than not be the arsehole. His characters are obsessed with all things anal and ass-worship: they sniff farts, knead and mutilate buttocks using fire, whips and chains, they sodomise, anally rape, conduct enemas, and eat more human shit than could be thought feasible (they even have the castle cooks change up their diet in an effort to find the optimal taste and texture).

The protagonist’s innate tendency towards sadism with their propensity for exploration, we get a steady descent towards hell. Quite literally: the final “passion”, the 600th of 600, is described as the “hell passion”, and is literally demonic. 120 Days quickly becomes a race to the bottom, in more ways than one. Like an Ordnance Survey map of Dante’s Inferno, no perversion is too vile or insignificant not to be charted, explained, discussed, and re-enacted.

Of course, The 120 Days of Sodom can’t be the first instance of these things happening. With the exception of perhaps one or two of the more creative passions that involve elaborate feats of engineering I get the sense that 120 Days Of Sodom is just a piece of categorisation. What’s perhaps most

De Sade is arguably ground zero for a series of seminal books that act as milestones categorising and laying out in fine detail the nature of evil, why it exists, and its consequences. After 120 Days comes Marx’s The Communist Manifesto, Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil, Solzenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, Browning’s Ordinary Men, and Chang’s The Rape Of Nanking. All show the rationale and the consequences of evil.

It means 120 Days is hardly unique; its bloodcurdling acts of untrammelled violence are revisited in The Rape of Nanking; the objectification of victims is revisited a million times in The Gulag Archipelago; and the desire to see the world burn for the sheer pleasure of playing in the ashes is the driving force behind the Communist Manifesto. But 120 Days stands as the odd man out among those other seminal books because it’s ostensibly a novel. But is it truly a work of fiction? De Sade wouldn’t have spent time cooking these passions up; he was a card-carrying libertine himself, arrested and thrown into the Bastille for crimes against children so debauched they even scandalised late-18th century France. Even so, De Sade couldn’t have committed all 600 of the passions listed in his book. The 120 Days of Sodom isn’t just a novel. It’s a record, it’s De Sade’s fantasy, and worst of all, it’s his confession.

I’d wager much of what I have that the rape gangs alluded to at the start of this essay haven’t read a great deal of De Sade (or much of anything at all), and yet the ordeals they subjected their captives to would quite easily sit somewhere among the Complex Passions and the Criminal Passions as described by De Sade. Much has been made of the fact of the gangs in Rotherham (and Telford, and Oxford, and Oldham, and Maidstone, and Blackburn, and and and…) were principally made up of Muslim Pakistanis, which would explain the depravity. While there clearly was a racial aggravating factor, the list of books above clearly shows that evil does not live in the breasts of one people alone. As Solzhenitsyn so cleverly observed, “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, not between political parties either – but through every human heart.”

Those paedophile rapists wouldn’t have read De Sade for inspiration, and neither did Marx or Nietzsche (the manuscript wasn’t published until 1904, twenty-one years after Marx’s death, and four years after Nietzsche’s). So it’s quite something that both Marx and Nietzsche arrive at the same conclusion as De Sade; that for the systematic dismantling of ancient institutions or people to be successful, one must first kill God.

Evil, for all the horror of its manifestations, rarely is conceived immaculately. It requires its justifications. The opening sixty pages of Crime And Punishment detail Raskolnikov’s justification for committing the brutal murder which psychologically destroys him after the act. Even De Sade’s four heroes have to formulate a rationale for doing the things they do.

“For – and why not say so in passing – if crime lacks the kind of delicacy one finds in virtue, is not the former always more sublime, does it not unfailingly have a character of grandeur and sublimity which surpasses, and will always make it preferable to, the monotonous and lackluster charms of virtue?“

But an attraction to vice isn’t enough. An attraction to vice might be enough to drive the libertines to exploring some of the Simple Passions, but if they are to proceed towards the demonic scenarios of the Murderous Passions, this is inadequate. To proceed into those depths, a more malevolent spirit is required. The Spirit of Cain. Nothing less than the dismantling, humiliation and erasure of God is the foundation upon which sheer evil can flourish.

The Duc goes on:

“I hate virtue, and never will I be seen resorting to it… I was still very young when I learned to hold religion’s fantasies in contempt, being perfectly convinced that the existence of a creator is a revolting absurdity in which not even children continue to believe. I have no need to thwart my inclinations in order to flatter some god; these instincts were given to me by Nature, and it would be to irritate her were I to resist them; if she gave me bad ones, that is because they were necessary to her designs. I am in her hands but a machine which she runs as she likes, and not one of my crimes does not serve her: the more she urges me to commit them, the more of them she needs; I should be a fool to disobey her. Thus, nothing but the law stands in my way, but I defy the law, my gold and my prestige keep me well beyond reach of those instruments of repression which should be employed only upon the common sort.”

The slightest religious act on the part of any subject, whosoever he be, whatsoever be that act, shall be punished by death.

Messieurs are expressly enjoined at all gatherings to employ none but the most lascivious language, remarks indicative of the greatest debauchery, expressions of the filthiest, the most harsh, and the most blasphemous.

The name of God shall never be uttered save when accompanied by invectives or imprecations, and thus qualified it shall be repeated as often as possible.”

Latterly, some of the passions themselves involve explicitly blasphemous acts; one instance involves pushing the Host of the Holy Eucharist into a priest’s anus and then raping him. There are several variations upon this passion, all related with fastidious precision.

Even this is not enough. The philosophical grounds thus established, a comprehensive othering of the victims must also take place. In Men The Behind The Sun, the film about Unit 731, the Chinese prisoners are called units of lumber; they are no more valuable than wood. The Japanese also spread stories about the Chinese being subhuman creatures only worthy of slaughter before their atrocious siege of Nanking. Jews have been portrayed as subhuman monsters, crooks or Christ-killers by various peoples over the centuries, from the ancient Babylonians to 21st century American university campuses. The Russian kulaks were portrayed as usurous, sniping thieves by the Bolsheviks. And the Pakistani rape gangs in Rotherham et al would refer to their victims as “easy meat”, “sluts” or “fair game”. And what of De Sade’s heroes? The night before the 1st of the 120 days takes place, the Duc addresses the terrified harem who have been kidnapped, procured, pimped and abducted for the libertines’ ruinous pleasure.

“Feeble, enfettered creatures destined solely for our pleasures, I trust you have not deluded yourselves into supposing that the equally absolute and ridiculous ascendancy given you in the outside world would be accorded you in this place; a thousand times more subjugated than would-be slaves, you must expect nothing but humiliation, and obedience is the one virtue whose use I recommend to you: it and no other befits your present state. Above all, do not take it into your heads to rely in the least upon your charms; we are utterly indifferent to those snares and, you may depend on it, such bait will fail with us. Ceaselessly bear in mind that we will make use of you all, but that not a single one of you need beguile herself into imagining that she is able to inspire any of the feeling of pity in us.

Your service will be arduous, it will be painful and rigorous, and the slightest delinquencies will be requited immediately with corporal and afflicting punishments…not that you have much to gain by this conduct, but simply because, by not observing it, you will have a great deal to lose.”

“What do I say [about] the life of a woman? The lives of all women who dwell on the face of the earth, are as insignificant as the crushing of a fly… we are not going to exist forever in this world, and the most fortunate thing that can befall a woman is to die young.”

With the rules in place, the philosophical foundations and justifications made, the victims suitably dehumanised, at last the game of Cain and Abel is ready to commence. The story of Cain and Abel is the first story to feature humans in the Bible (Adam and Eve are quasi-mythological creatures). Their story is the oldest one humans can remember. A story of the destruction of the ideal. De Sade didn’t chronicle anything new; he just put in the parts that the Bible left out.

The 120 Days of Sodom is the worst sort of fantasy; the sort of fantasy that simultaneously imagines and chronicles the destruction of humanity, one person at a time, by degrees. It shows the endgame of a godless world. De Sade hit the target before Nietzsche. If you kill God, all you’re left with is chimps slowly destroying other chimps. And even the novelty of that soon wears off.

“‘There are,’ said Curval, ‘but two or three crimes to perform in this world, and they, once done, there’s no more to be said; all the rest is inferior, you cease any longer to feel. Ah, how many times, by God, have I not longed to be able to assail the sun, snatch it out of the universe, make a general darkness, or use that star to burn the world! Oh, that would be a crime, oh yes, and not a little misdemeanor such as are all the ones we perform who are limited in a whole year’s time to metamorphosing a dozen creatures into lumps of clay.’”

Writing about a book like The 120 Days Of Sodom – hell, even reading it – is to peer into the abyss. But upon further reflection, there is a glimmer of hope to be gleaned from this most awful of texts. For darkness to exist, so must the light. For 120 Days to be so awful, there must be some virtue against which to measure it, and balance it out. We are not bound to the path of destruction. To kill God, God must have existed in the first place.

Unusually, I’m going to give the last word to myself. The following passage is from my forthcoming novel The Green Man.

“Without these trials, there would be no need for inquisitors and judges. Martyrs only become martyrs because tyrants exist. All is merely light and dark, opposing sides of a coin… the cost of triumph is that [evil] must exist. So look to the Lord, Jacobus. He sees your true path.“