It’s been said that the characteristic difference between left and right wing politics is the question of borders; generally speaking, the more conservative one is, the less one is inclined to keep the borders open, until you get to the extreme end where the ideal number of people crossing the border is zero. And vice versa for the left-wing, whose ideal border policy can be described in two words: Open Door (although I’m aware that the descriptors “left” and “right” might be losing their meaning as the political landscape undergoes its current changes. But that’s another topic for another day).

The border question reflects deeper attitudes towards information in general. If societies are systems – and they are – then people represent information. Information on its own terms is neither good nor bad; it requires judgment to determine what information is useful, but also to determine which pieces of information are potentially dangerous. If we scale this example back up to people, you can see why getting this policy right is among the thorniest of problems in politics: a society requires new information in order to generate new ideas, innovate and enable trade. On the other hand, allowing too many people to cross the border means it becomes increasingly difficult to establish which people have altruistic goals in mind, and which have more malevolent aims. Because of the potential danger from the outside world, societies can be tempted to seal up the border, and let not a single threat through. But that can bring its own dangers.

I’ve been thinking about the Gormenghast trilogy recently, and especially its mad, pseudo-Gothic fantasy first book, Titus Groan. Sometimes a culture is too sick to survive. It either allows the barbarians in at the gates, or it builds its walls so high that it withers and dies. The eponymous castle of Gormenghast is of the latter persuasion. It is a vast, sprawling metropolis, less an ingot of stone thrust up in the name of a nobleman than a civilisation in its own right. Its walls stretch high and wide, an impregnable border between worlds.

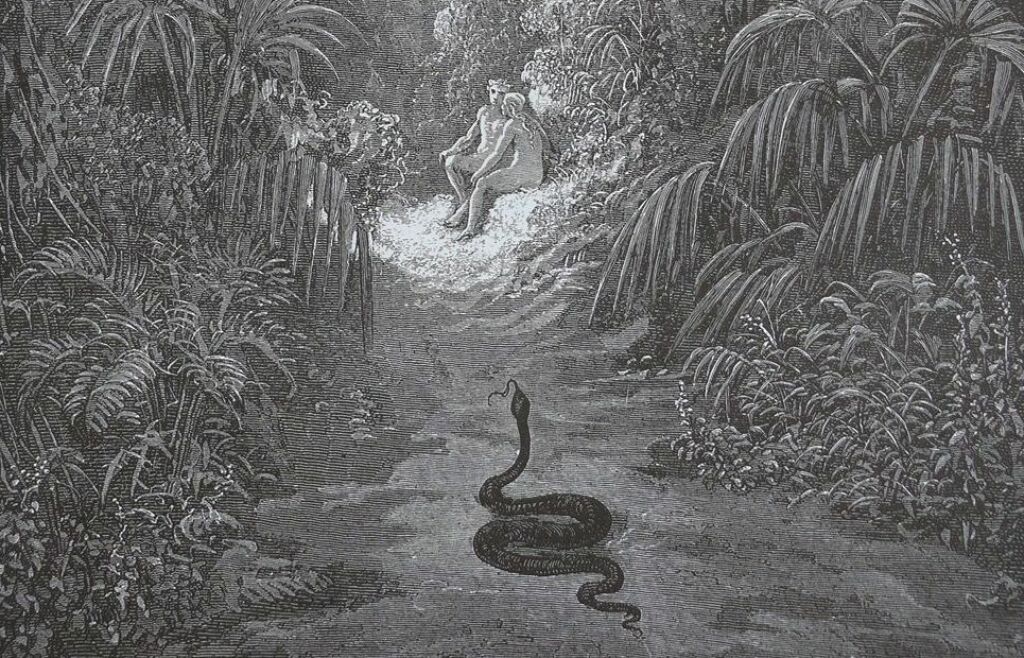

Well, the walls of Castle Gormenghast stretch high, and keep the barbarians out, but I’m reminded of the story of Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden. It’s worth remembering that the word paradise means “walled garden”. Paradise may well be walled (and Gormenghast is a long ways gone past paradise) but that doesn’t mean occasionally a snake can’t get in. And all it takes is one snake.

Gormenghast isn’t just conservative, but it isn’t authoritarian either. It’s a society that’s gone to seed, its best days far behind it and without any inclination or ability to change. It serves an example of a society that has permitted no new or fresh information or people to pass into its walls, and as a result it and its population have become ossified. It is a society that gets by on ritual alone, but where the rituals have long since been decoupled from their religious foundations, leaving them just as joyless functionary tasks overseen by a gerontocracy which has forgotten their meaning. There is order, but without ethics. Objectives, but without purpose. And everywhere atrophy and sclerosis abounds, as though a wizard has cast a spell to turn them all to stone, but over several hundreds of years.

We see the librarian Sourdust, a desiccated gerontion, preparing for the ceremony. The library is a place of great symbolic importance in Gormenghast; it of course represents culture, and the history of the place, but Sourdust, like everyone else int he Castle, has no real idea of what’s in any of the books. The same goes for his son and eventual successor, Barquentine. He understands his job well enough, and performs it with well-practised efficiency, but has no idea why it is done other than the fact that this is way it has always been done. Here we have a society that sees its history but doesn’t understand it, and therefore has no way to protect it, other than preserve it for its own sake. Sourdust is an emblem of a society’s people who have become its mere curators, keepers, its nightwatchmen, rather than people who actively engage in it, keep it alive. The library is of great importance, as we see later on.

Things are the way they are because that’s the way they always were. The living fossil Flay the Footman, and the monstrously obese chef Abathiar Swelter, share a pulsating hatred toward one another that is never fully explained. It simmers, like one of Swelter’s revolting dishes of slop, until it boils over into a surreal explosion of brutal violence. Why? We are never told. They began as enemies, and they go out as enemies. Flay learns that Swelter wants to kill him. Why? Don’t know, but it escalates from there. If you can imagine the sorry idea of the story of Cain and Abel, but where both characters are Cain, you get somewhere close.

The twin sisters Cora and Clarice are stupid to the point of intellectual disability. They serve no one but themselves, and believe themselves deserving of everything merely because of the coincidence of the station of their birth. The suitors fighting for Fuscia’s hand kill each other. The characters are certainly colourful , even ostentatious, but despite their vivid personalities they are ossified, decrepit, dilapidated, somehow bounded physically to the very walls of the place. The vast majority of these characters of stone, ritual and brick are utterly incapable of change. No one works, everyone is either arrogant, stupid or both, it is rife with conflict and everywhere there is dust, dust, dust. This is a problem for the society, but also the drama – characters without arcs don’t make for great drama, right?

All of which is to say that this once-great castle-city – and the story – is crying out for an agent of change. Revivification is a core theme of myth and fantasy. The corrupted land is in need of regeneration and renewal, which arrives in the unifying Arthurian figure foreseen in prophecy and lore. Peake knows this, and delivers us not one but two agents of change.

The first is the titular character, Titus Groan, who is an infant, and who does not really affect the story until the end of the first book, when he is a toddler. In true fantasy tradition, his coming is foretold, and when the Earl of Gormenghast’s wife falls pregnant, it seems there is at last some sliver of hope that this antediluvian society may creep and crawl into the next generation, delaying the inevitability of extinction for a little longer. When we do see him we are shown the sight of the birthday rituals; they are less pomp and circumstance than ghastly automated motions. Before he can walk Titus is thrust into the various rituals of the castle, each one meticulously planned. We see the first hint of change when the blessed child drops the precious artefacts into a lake at the moment of his coronation.

But even Disney can’t make a two year-old the full agent for change in a story. Enter Steerpike, the kitchen boy.

As mentioned, most of the characters are by turns vain, arrogant, closed-minded, gormless and aloof. They are also, with one or two exceptions, skull-crushingly imbecilic. With no incentive to change or grow or learn, and only waking each morning to slog through the same rituals as the day before, they are a dull-minded lot. Arguably only Fuscia, the Earl’s daughter, displays anything approaching a sympathetic personality; she’s understandably naive, and slightly dim, but she’s sweet, innocent, and believes that there is something more than the endless drudgery of Gormenghast. Which makes Steerpike’s introduction all the more clinical and striking. Here’s a young lad we see who has a bit of wit about him. No sooner has he skipped away from the kitchen with carefree laissez-faire, than he’s manipulating Flay into carrying out some oddjobs for the footman. And so begins Steerpike’s ascent through the echelons of power within the castle walls. He is so contrary, so active and artful, so clever and quick that one immediately roots for the lad. He takes advantage of the castle’s denizens in order to gainsay influence and power for himself. Good for him!

And yet… he doesn’t want to just make something for himself. He is the only one who sees the castle for what it is: a bastion of the status quo perpetuating itself for no good reason. He wants it gone. He’s an agitator, a revolutionary, and once he meets young Fuscia after swinging through her bedroom window like a swashbuckling antihero, he’s displays a dangerous sexual swagger. Peake’s portrayal of Steerpike is very clever. Against this cast of grey half-skeletons here’s Steerpike, full of piss and vinegar, and with the canny observation that in this strange old place only a handful of people have all the power, and for no obvious or fair reason.

So, as he slowly and fastidioudly tortures and destroys a spider in the castle gardens, Steerpike decides to reveal to Fuscia what is really driving him.

“E Q U A L I T Y,’ said Steerpike,’ is the thing. It is the only true and central premise from which constructive ideas can radiate freely and be operated without prejudice. Absolute equality of status. Equality of wealth. Equality of power.” – Mervyn Peake, Titus Groan.

Equality! The word is even capitalised by Peake. This scene is the crux of the entire novel. When Steerpike the kitchen boy utters that fateful word it feels completely logical, the only obvious conclusion to be drawn from living in that flat, ossified world. And yet it’s immediately undercut by Steerpike’s spiteful and unnecessary torture of the spider. Steerpike knows that Equality, taken to its organic conclusions, becomes a terrifying equaliser, a weapon to be wielded to help him acquire power for himself. He wields it with venom and spite.

There is a low cunning to Steerpike; he is spiteful and manipulative but he only needs to be slightly smarter than the next smartest person in the Castle, and the next smartest person – perhaps the mad Doctor Alfred Prunesquallor – isn’t exactly the sharpest sword in the armoury. Nevertheless, like all revolutionaries he exhibits dynamism, and a romantic call to adventure – he is a seventeen-year-old boy after all, and this combination of attributes is very attractive to Fuscia.

In a society going nowhere Steerpike presents himself as the heroic saviour. He rescues the Earl’s family from the fire in the library, a fire which he started. He feeds off the corrupt, arrogant stupidity of nobility who have done nothing to earn that status. And so we return to the symbolic importance of the library. A rich metaphor for that society’s history and culture, burned down in a trice by a manipulative power-seeker who presents himself as the future. Even The Guardian, the standard-bearers for left-wing activism and agitation, recognise Steerpike as a villain and label him the “Great Manipulator“. I bet you never look at all those people who throw orange paint at old masters and pull down statues in the same way again, eh?

It seems unbelievable that Peake’s magnum opus came a full two years before Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, and eight years before The Lord Of The Rings. Titus Groan was published in 1946, just after the War. Peake comes to a revelation that is so prescient it almost defies belief. A year previously, Peake was among the first British civilians to visit Bergen-Belsen, the infamous Nazi concentration camp where over 70,000 people were killed. After the British 11th Armoured Dvision rolled in, Peake was among the first civilian visitors. He saw emaciated, tortured prisoners too sick to move died where they lay, even after liberation. Neither station, wealth, success nor title defined them. Here was equality pursued with ruthless efficiency, the legs pulled from the spider one by one by one. Steerpike is the embodiment of the corruption of left-wing politics, a corruption of fair representation of the working man into a movement to burn everything down just for the sheer revelry of it. In that sense he’s a classical narcissist, someone who seeks the fame and adulation that goes along with an esteemed reputation, but without wanting to do any of the work to acquire it. So he uses short cuts, manipulation and chicanery to achieve those ends instead.

Yet the point is that Steerpike is exactly the change that Gormenghast deserves. The castle’s sterility means that the novelty of the Steerpike’s emergence as an agent of change can’t be differentiated from his malevolence. It is a society too sick to survive the onslaught brought about by this chaotic demon. As a result change is not a gradual and organic process as it would be in a healthy society, but a violent, confusing lurch into something unrecognisable. Steerpike’s novelty makes him difficult to combat. Using propositional-based logic Steerpike is able to confound, seduce or manipulate the bewildered fossils around him and elevate his station accordingly.

Writing as Peake did at the end of the Second World War it would be tempting to think of Gormenghast as an allegory for England (or, more accurately, the British Empire) itself; a tired power on the wane, too exhausted from past battles to rouse itself to fight or even recognise a more seductive enemy stirring within its walls. For me the timings don’t quite add up for this; yes, Peake would have been traumatised by his discoveries at Belsen, and jaded by the state of Britain at the end of the war, but Titus Groan was published in 1946; surely the bulk of this book would have been written before the war had ended and Belsen had been discovered.

More likely that Peake would have drawn from the more distant history from the aftermath of the First World War, when the lines of the European map had been redrawn, various tired powers like the Ottomans, the Prussians and the Kaiser slipped into nothingness. Russia had succumbed to the Bolshevik revolution, where a hollow and decrepit tsarist rule was unable to save itself from the seductive modernism of Marxist-Leninism. Peake was familiar with Malcolm Muggeridge’s dispatches from the Soviet Union under the gruesome early years of Stalin’s rule, and surely that would have been the trigger for the creation of Steerpike, ostensibly a heroic figure, but only to those who can’t see him for what he truly is.

Gorgenghast is, then, not England, or Russia, or anywhere else explicitly. It’s a sophisticated political critique and a warning to all societies: if you become too arrogant and comfortable, your society becomes vulnerable, and perhaps even too sick to survive. And the enemy won’t come in the form of barbarians at the gates, but the ones who say they represent progress, equality, and freedom from the past.

In the sequel, Gormenghast, Steerpike gets his comeuppance, but not before his work is done. Titus grows into a world that is decoupled from its own history. There is no library, the books are burned. By the time we get to Titus Alone, the third book in the series, we see Titus as someone who is completely thrown and detached from his own culture and origins. The third book is usually viewed by readers as completely tonally off from the first couple of books, but if one views Castle Gormenghast as a sick society in its death throes, it makes perfect sense. And it makes even more sense that Titus should not flourish in that brave new world but flounder, unsure of himself and with nothing to anchor him culturally.

We can’t say we weren’t warned.

Discover more from Dan Jones - the Official Site

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.