All civilisations have had people dedicated to learning, and the furtherment of human knowledge, effectiveness, efficiency and technology. But that isn’t necessarily science, and that doesn’t mean that every society can be, or has been, scientific.

One only has to look at the incredible advances in technology made since the advent of real, Cartesian scientific thought and reasoning, to see the difference between what a scientific society can achieve in contrast with the pre-scientific world up to around the early 1600s.

But the right conditions need to be in place in order for science to flourish. It’s assumed, certainly by most (but by no means all) scientists that the fundamental nature of the universe is that of a place to be observed. This is certainly the perspective of Brother Jacobus, the protagonist of my new novel The Green Man. Despite being a man of God and a Holy Inquisitor, his starting position in the story is that everything in the world can be fathomed with logic and reason.

But there’s a more profound level to the universe, which is as a place of action. It’s by acting in the proper way, over many many generations, that the principles and structures governing modern scientific thinking were established and honed. Essentially, the question of why we do science. The Cartesian essence of science was that it was detached from moral frameworks and bias, so as not to corrupt its procedural function. But that doesn’t answer the question of why it was desirable to do that in the first place.

It’s self-evidently true to us that a corruption of the scientific process is undesirable, because the results would be skewed by scientists’ own personal or political biases. But why is that in itself desirable?

As far as I can see it’s that having a pure, unibiased scientific enterprise – acquiring better results – is the optimal pathway to exploiting the science in new technologies, making things better for people. But why make things better? Again, the answer seems to be self-evident. The world is full of suffering, injustice, and cruelty. Wouldn’t it be great if we could alleviate some of that through and and improved technologies? Of course. But why bother making things better?

The use of the word better here implies relativity. That there is a scale of “goodness” with respect to the way things are, and there is inherent value in pushing the tiller further along the “better” end of the scale. OK, so then why do we want things to be better?

Scientists can answer this question to a certain degree, but at some point the question becomes uncomfortable, because at the very bottom of the justification for proper, ordered scientific procedure, the rationale becomes decoupled from the science itself. At some point the question becomes one of values, judgment, ethics, philosophy, and at the deepest levels, religion. Despite the scientific procedure being detached from individual values and judgment, individual scientific endeavours are guided by the individual’s own values and judgment. No scientist can study all the scientific disciplines, so they specialise; and the more niche the area, the deeper the specialty can drill.

That’s a value judgment, deteremined by the personal values and biases of the individual. A marine biologist investigating the mating patterns of a particular type of shark is very precise endeavour, but will be an almost inexhaustible mine of information for the keen digger. Ditto theoretical physics. A counterargument might be that at the individual level somebody can be guided into their niche field by their own values – ie what’s important and relevant to them – but the scientific enterprise per se is one step removed from that. But that’s not true either; science per se is enabled by cultural values and judgment. Science happens when a culture has decided that science is worth pursuing. When you drill down deep enough you get to the realisation that that’s because people matter, and we’re worth improving.

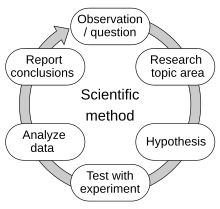

These ideas are rooted in the idea of adventure, calling, perception, and values. They are biological in origin but instantiated thorugh behaviours: firstly ideation (the conception of an thought or idea); action (acting out that idea); comprehension (understanding the consequences of that action), and codification (logging the results for future iteration, or warning). Once upon a time we could only do this by literally acting things out. Our cortical evolution evetually allowed us to do this through thinking. We then were able to capture the results through one of our most ancient forms of technology: storytelling. Science, then, is itself a form of storytelling. What else is the scientific enterprise but the establishment of ideation (hypothesis); action (experiment) ; comprehension (observation); and codification (capturing the results)? It’s a great story to tell.

Another counterargument might be that because all cultures have developed the technology of storytelling, this mirroring of the scientific enterprise must be inevitable. But that’s also not true. The storytelling architecture may be similar, but leveraged through the intrinsic values of that particular culture. Just as (a) culture establishes the preconditions for science, it can wipe them away. To see that, one only has to look at the cynical Lysenkoism espoused by the Soviet Union, which imprisoned thousands of biologists to clear the way for a new approach to genetics and agriculture derived from a perversion of the scientific method. The Chinese Communists also got hold of this wizard wheeze, with predictably catstrophic results for their agricultural yields. Or we could look at the desire to return to antediluvian models of society exhibited by the extreme ends of fundamentalist Islam, whose more bloodthirsty advocates yearn for a return to something approximating 9th century Syria. For a less brutal example we could look at the Amish and their rejection of technology, leaving them in a time-capsule, largely unchanged for the last two centuries. Or, to return to biology, we could look at the recent phenomenon of untrammelled trans-activism in the west, that has, like the Soviets, swept away everything we know to be true about human biology and sexual evolution in the name of political progress. For those outspoken scientists who defended their work, they quickly found that freedom of speech was a fundamental tool in making sure that real science could flourish.

Culture trumps science. In my story Brother Jacobus finds this out, the hard way.

Discover more from Dan Jones - the Official Site

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.